Recap of 92Y Talk: David Brooks on Defining Your Moral Genius

by Luvon Roberson

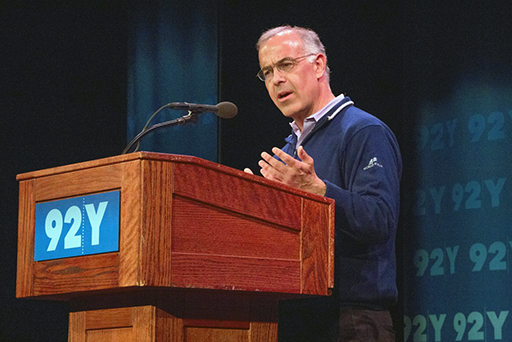

“He’s currently teaching a course in humility at Yale,” is how David Brooks, New York Times op-ed columnist and “PBS NewsHour” commentator, is introduced to the 800 audience members at 92nd Street Y on Sunday, March 9.

To loud acclaim and applause, Brooks walks onto the stage and begins his talk, “Genius, God and Morality,” part of the 92Y 7 Days of Genius Festival.

As his talk unfolds, it becomes apparent that such seemingly diametrically opposed concepts – humility, on the one hand, and Yale University’s legacy of privilege and elitism, on the other – are at the root of Brooks’s take on moral genius.

Indeed, he invites the audience to join him in taking an unflinching look at our current culture’s obsessive focus on success and the external life, which he calls “the resume self” or Adam I. In dynamic opposition to that, says Brooks – a self-named “dualist” – is our focus on meaning, serving others, humility, which he calls “the eulogy self” or Adam II. Brooks frames moral genius as humility and as “character.”

Over the next 90 minutes, Brooks sets forth the constructs of moral genius and character, and along the way, names historical figures he views as exemplars of character. Brooks is not merely “name-dropping” the famous and celebrated. He is drawing on the power of naming as in Biblical genealogy, religious ritual or incantations to long-honored ancestors and orishas. In offering these examples, Brooks stands on his conviction that “biography is our essential teacher, not philosophy.”

What is moral genius or character?

“We live in a culture that nurtures Adam I,” he says, before adding that American sociologist Christian Smith views our society as having “no moral vocabulary.” In contrast, moral genius or character is Adam II, “not loud or puffed up. It is reticent, quiet, not broadcast.” And character resides “in a core piece of oneself. It is how you make disciplined choices. It is engraved, deep inside. A person of character has depth, is intellectually large.”

Who exemplifies moral genius and character?

Brooks begins with George Marshall, the only man to serve as both U.S. Secretary of State and Secretary of Defense. Marshall was a WWII hero as head of the U.S. Army, a leader in establishing NATO, and a Nobel Laureate. Marshall also is memorialized for his superlative leadership in the economic recovery of Europe after WWII, which is named the Marshall Plan.

But, Brooks doesn’t recount any of Marshall’s career or Adam I accomplishments. Instead, he chronicles Marshall’s evolution in building moral genius and character, following him from his early childhood and youth to his final years, particularly, Marshall’s one-hour retirement from public service as well as Marshall’s choice – at a defining moment in his career – to eschew self-promotion.

Brooks shows how Marshall’s dedication to leading a life of character over self-advancement could cause him suffering and pain. One wrenching instance of his choice: Marshall, a global strategist, was asked four times by President Franklin Roosevelt if he wanted command of Operation Overlord – the code name for the Battle of Normandy, commonly known at D-Day. Although Marshall coveted the command, he refused to influence Roosevelt’s decision, saying “..never think about self over the cause.” Marshall is crushed when the president chooses Dwight Eisenhower for the post.

In his early years, Marshall’s father, a highly critical, judgmental and demanding man, scarred young Marshall’s self-esteem and sense of agency. Brooks believes that it is through Marshall’s sheer, unrelenting determination to master his shortcomings and to discipline what he perceived as his faults that Marshall demonstrates morality.

Brooks moves onto Dorothy Day. Overcoming an early life of controversy in the 1920s, one punctuated with love affairs, an abortion, and branded a social anarchist, Day moves beyond her life crises to what Brooks maps as a life of “surrender, from dissolution to years of discipline.” Out of chaos, she builds a disciplined, focused life, eventually creating The Catholic Worker and settlement houses and soup kitchens for the poor and homeless.

A. Phillip Randolph and Dwight Eisenhower are among the others named by Brooks. He notes that Randolph’s responses to racism over the course of his life were key to his development of character. Over time, Randolph combated his anger for racists and the humiliation of inferiority he suffered at the hands of racists to a life of rectitude. Brooks states that Randolph’s elocution was perfect as was the dignity of his manner and moral conduct. Indeed, in Randolph’s humility, he refuses the nomination to the Nobel Peace Prize.

Turning to Eisenhower, Brooks quotes Proverbs 16:32, He who controls his temper is better than a war hero, he who rules his spirit better than he who captures a city. Brooks notes that the 34th president battled anger by replacing it with “a veneer of affability and passion.”

Not born with it? How do you get it?

According to Brooks, “No person can attain self-mastery on his or her own. You must put yourself in dependence to God, religion, others…institutions, another authority, a profession or craft.”

Moral genius and character is only possible when “Adam I bows down to Adam II.”

As if anticipating the questions to come from the audience when the lights come up, Brooks ends the talk by offering a concrete way to begin building moral genius and character in yourself: “Go online and get pictures or buy a bunch of postcards of dead people you admire and put them on the wall. Lead your life like they’re watching you. It may help. I don’t know.”

Enjoyed this article?

Get more reviews of top events and be the first to know about new lectures by joining the Thoughtlectual community at no cost. Click here to join.

Discover More

Discover More